Adventure Travel Blog

Looking for Something Specific?

Our Blog Posts

12 MONTHS, 12 MOUNTAINS

In celebration of World Mountain Day, we've created a calendar for the year to make it easy for you to plan your next mountain climb in the...

Mount Aconcagua Trip Review

January 2016 This year we had a team of twelve clients from four different countries – Iran, Ireland, England, South Africa and Argentina –...

Alcey’s Survival Skills Course at Lupa Masa Jungle Camp

In celebration of International Rural Women’s Day, we’re talking about Alcey Kangit Gordon! Alcey is from Kiulu, a small rural village in...

Why Kilimanjaro is a Great Mountain for Any Bucket List

Climbing one of the world’s tallest mountains is not a decision to be taken lightly – it will take endurance, a decent amount of fitness...

Kilimanjaro Compared to the Other Seven Summits

The 'Seven Summits' is a challenge first proposed and then completed by Richard Bass in 1985. The 7 Summits consists of climbing to the highest...

Walking Holiday in the Sierra Nevada

A new destination to the Sierra Nevada in southern Spain beckons. What a beautiful place and a lovely hotel we found... in a small village...

What’s The Highest Mountain in Europe?

Its summit is 18,510 feet (5642 meters) above sea level and it is located in Russia. However the mountain itself - including the glaciers...

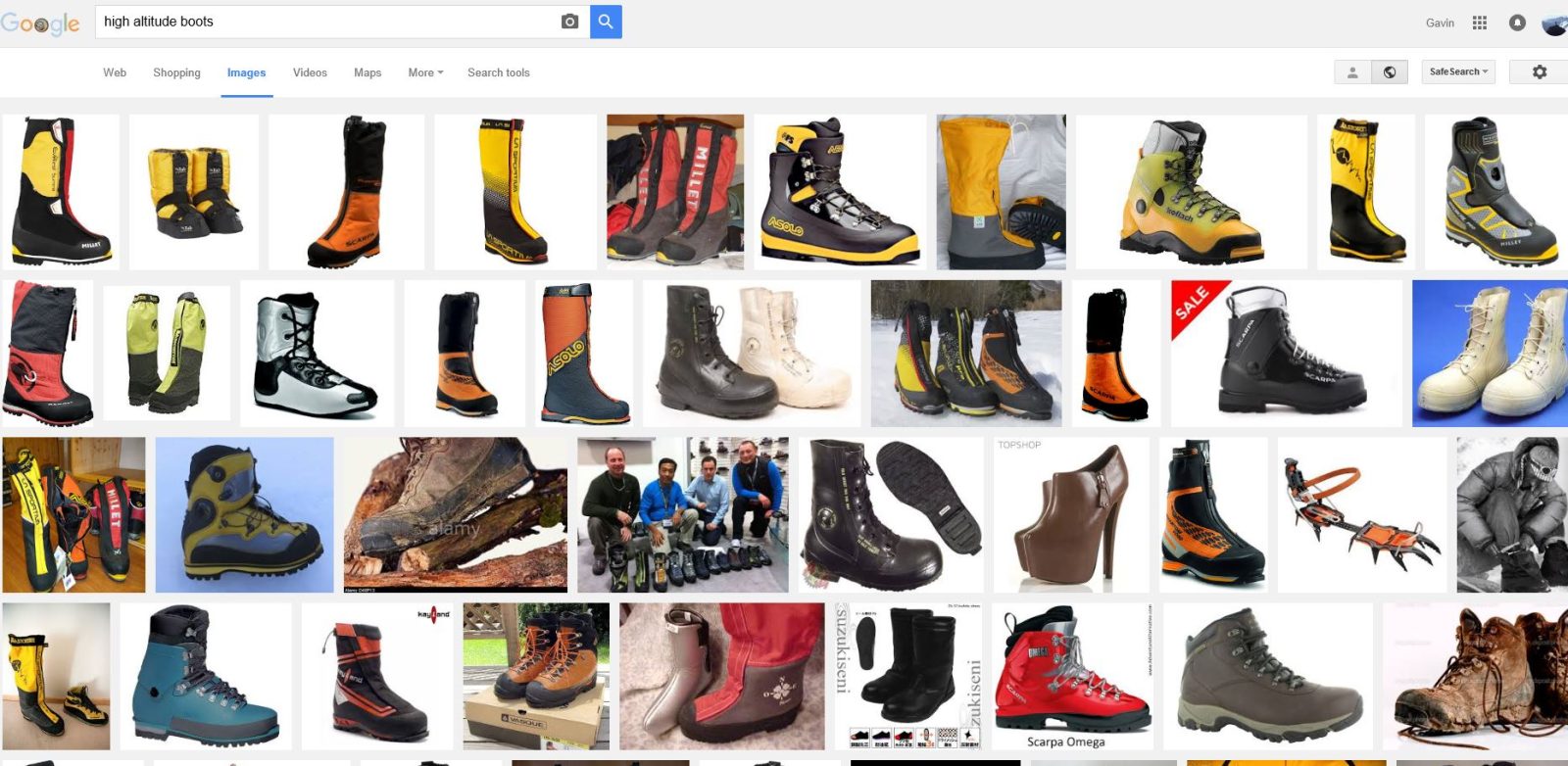

Choosing High Altitude Boots

Twenty years ago things seemed a bit simpler, climbers chose from a narrow range of leather trekking boots and generally a pair of 'double mountain'...

Great Reasons to Visit Bulgaria

With more and more people getting out in the mountains and using holidays to trek and climb it is becoming increasingly difficult to find good...

Accommodation in Embu Guest House

Anyone visiting Embu on a Medical Elective or to volunteer with the Moving Mountains Trust will spend time in our Adventure Alternative...

How challenging is a Maliau Basin Trek?

The Maliau Basin has only partially been explored, leaving over 50% of the area completely untouched. It is conservation reserve of dense, untamed...

Hammock Life – Volunteering in Borneo

Nothing quite beats waking up to the sound of the rainforest while gently swinging in a weightless cocoon; the dappled sunlight...

Accommodation in Western Kenya

Anyone visiting Western Kenya on a Medical Elective or to volunteer with the Moving Mountains Trust will spend time in our Guest House or...

How can I Climb Kilimanjaro for Charity?

We often get asked, ‘how do I climb Mount Kilimanjaro for Charity?’ and the answer is easy, call us to have an initial talk about...

Huts on Mount Elbrus

Years ago when I was guiding clients with my Russian friend Sasha Lebedev to climb Mount Elbrus during the ‘perestroika’ period after...

Happy New Year Nepal!

Although our calendar, the Gregorian calendar, is recognised in Nepal they also have others which are also used so it's currently the...

Looking for Country-Specific Blogs?

You can access our captivating blog posts on adventure holidays, particularly treks and mountain climbing, from anywhere in the world. Adventure knows no borders. Our blog becomes a virtual gateway to explore the world’s most thrilling landscapes and experiences from the comfort of your own location. Embark on a digital adventure today!